In 2011, Audrey Tobias refused to provide Statistics Canada with a filled out copy of her census form, as mandated by law. Her decision, and her decision to stand by that decision, led to a trial in which the 89-year-old faced jail time. Although Tobias stated that her act was protest against the use of US military contractor Lockheed Martin to process the forms, and not against the mandatory nature of the census itself, this was really a trial of the government’s power to compel citizens to provide it with private information. As Tobias’ lawyer, Peter Rosenthal, argued, compelling Tobias to fill out the form on threat of jail was a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights, and its provisions for freedom of conscience and expression.

The judge in the case, Ramez Khawly, rejected Rosenthal’s argument, but found a way to find Tobias not guilty anyway on the basis of his doubt about her intent in not filling out the form. Perhaps sensing the outrage that might ensue over punishing an octogenarian for a non-violent act of civil disobedience, Khawly was nevertheless too fearful, or obtuse, to uphold an argument that would set a highly inconvenient precedent from the standpoint of the state. The judge both justified and exposed his particular mix of cowardice and compassion by asking, “Could they [the Crown] not have found a more palatable profile to prosecute as a test case?”

I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised by the judge’s politically expedient decision. What shocks me is the reaction of many regular citizens, and in particular of some fellow statisticians. Let me be as clear as possible about this: support for the mandatory census is a moral abomination and a professional disgrace. It should go without saying that informed consent is a baseline, a bare minimum for morality when conducting experiments with human subjects. Forcing citizens to divulge information they would otherwise wish to keep private, on pain of throwing them in a locked cage, does not qualify as informed consent!

There is no point here in arguing that what’s being requested is a minor inconvenience, or an inconsequential imposition. Informed consent doesn’t mean “what we think you should consent to.” More than anything else, statistics is about understanding the inherent uncertainties in measurement, prediction, and extrapolation. Just because you might not object to answering certain questions, gives no reason to assume the universality of your preferences. Finally, note that to at least a small group of revolutionaries, the right not to divulge certain information to authorities was so important that it was written right into the Bill of Rights.

Besides the argument that the census in minimally invasive, I’ve also heard it argued that the value of obtaining complete data outweighs concerns of privacy and choice. To this I say that our desire, as statisticians, for complete and reliable data, isn’t some ethical trump card, nor is it the scientific version of a religious indulgence that purifies our transgressions.

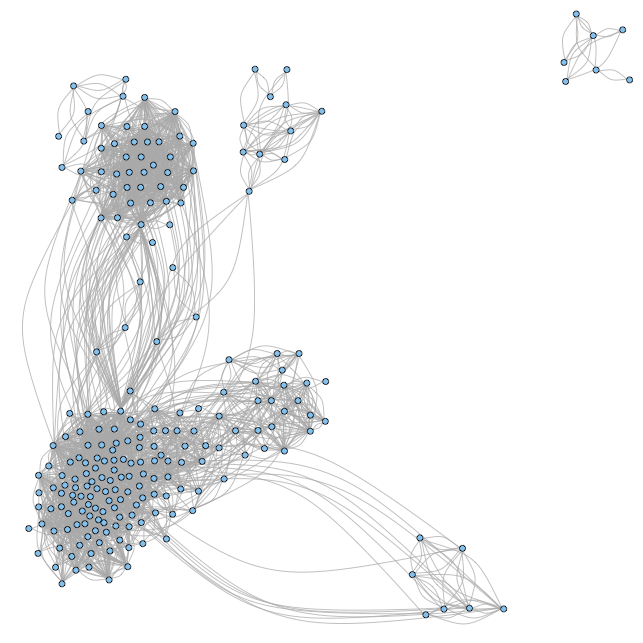

Dealing with incomplete and imprecise data isn’t some unique problem that can be overcome at the point of a gun, it’s the very heart and soul of statistics! In the real world, there is no such thing as indisputably complete or infinity precise data. That’s why we have confidence intervals, likelihood estimates, rules for data cleaning, and a wide variety of sampling procedures. In fact, these sampling procedures, if properly chosen and well executed, can be more accurate than a census.

I call on all those who work for StatsCan or other organizations to refuse to participate in any non-consensual surveys, to stand up for their own good name and the good name of the profession, and to focus their energies on finding creative, scientifically sound, non-coercive ways to obtain high quality data.